Content Warning: Discussion of fatphobia, diet culture, bullying, disorder eating

Spoilers for Maebashi Witches

Maebashi Witches has been one of the brightest hidden gems of 2025 so far, with its generic-at-first-glance character designs hiding some creative, kaleidoscope visuals and a script that excels at using its magical girl theme to tackle social issues. Its series composer, Yoshida Erika, is best known for adapting Bocchi the Rock!, but she also helmed the live-action adaptation of BL office romance Cherry Magic!, which introduced a very well-received aroace character. Yoshida’s talents also shine in Maebashi, which isn’t so much about revolutionizing the world as imagining achievable ways that everyday girls can make the world a better place. And nowhere is the show stronger than in its exploration of fatphobia.

Fatness in anime and manga is, of course, a complex topic, but there are several recognizable trends that often overlap with Western tropes. There’s the trope of a fat person as comic relief, where their body is the punchline—take How Heavy Are the Dumbbells You Lift?, for instance, which relentlessly dunks on its heroine for being a whopping 120 pounds while also zooming in on the hem of her skirt and her boobs; or Persona 4’s Hanako, whose mean girl behavior is implicitly twice as audacious because she’s (gasp) not hot. Then there’s the trope of the fat villain, a staple of fantasy and various fight-the-power stories that use fatness to signify corruption and greed–consider the Witch of the Waste or Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure’s Polpo. Even pointedly progressive and excellent titles like Yuri!!! on ICE and Dead Dead Demons’ Dededede Destruction use weight gain as shorthand for moral failing, with the characters needing to be bullied back into a trim physique. Meanwhile, fat action heroes like Fatgum and Choji tend to slim down to achieve a chiseled physique when in their most powerful form.

There are also titles that have tackled societal fatphobia in more nuanced ways. In Clothes Called Fat and Helter Skelter depict women whose lives spiral into ruin because of the crushing weight of societal beauty standards, and both are painfully real but tragic tales. There’s also the “former fat” narrative, in which a character was previously fat and suffered trauma from fatphobic bullying but is depicted in the present narrative with a conventionally attractive character design. These storylines can range from nuanced character studies (Skip and Loafer) to fodder for cheap jokes (Laid-Back Camp). While there are generally more positive examples, with normalized depictions of fatness starting to appear as well, it’s these stories about fatphobic bullying that Yoshida is most directly interfacing with.

Maebashi Witches wastes no time jumping in on the topic, either. The first episode sets up the premise, in which a group of girls run a wish-granting shop as training to one day become full-fledged witches. Their magic takes the form of musical numbers, and they won’t be able to use magic in the real world until they’ve finished their training. All of the girls get to know one another by passing out fliers and courting customers…except for the acid-tongued and fashionable Azu, who is never seen outside the shop. Once it’s finished that simple set up and a “practice” customer, the shop meets its first real client: a plus-sized fashion model named Rinko. Azu immediately lashes out at her, accusing her of wanting to use magic to become thin the “easy way.” It is not enough in society’s eyes, after all, to simply lose weight. The advent of GLP medications was just as quickly followed by jabs about “Ozempic face,” and jokes about liposuction are as old as the procedure itself. It is not enough to be thin; for the crime of having been fat, one must put on a performance of suffering. Mincing no words, Azu declares that she “hates fat people” before running out of the shop and back to her own room.

It soon becomes clear that Azu’s hostility is born of self-loathing: she is fat herself, and wants to become a witch in order to make herself thinner with magic. With that, she’s able to present herself as thin for the other girls, but it comes at the cost of being unable to leave the shop and leaves her constantly exhausted. It echoes the cost of existing publicly as a fat person, where mundane activies—eating, exercising, shopping—come with a level of implicit or vocalized judgment from the outside world.

Rinko returns to the shop, and the episode hits multiple points deftly: Rinko has had a larger body frame since childhood; that despite her confident persona, Azu has stopped going to school to escape bullying; and that while she still faces fatphobic comments in her daily life, Rinko’s current struggle has nothing to do with losing weight. Rather, she’s troubled by the pigeonholing projects she’s being offered. Finding work as a plus-sized model has involved compromising her goals and accepting jobs that make her the butt of a joke, with the latest career-advancing shoot she’s been offered centering around a pig costume.

The highlight of the episode comes when Rinko and Azu are able to talk alone, with Rinko gently intuiting Azu’s own body image issues. What follows feels both like a conversation to one’s younger self and to the next generation and the fact that both women have experiences allows the conversation to blossom with more nuance than if it were simply a fat person educating a thin one. Azu’s self hatred and trauma weren’t fixed despite a literally magic cure, because fatphobia is so much more insidious than that. Her compulsion to lash out at Rinko mirrors how “former fats” often try to shore up their new social position by deriding other fat people, and Azu feels wracked with guilt because she also deeply admires Rinko’s confidence–which only makes her feel more like a failure for hating herself. These are struggles Azu is only able to share when she meets an adult shaped like herself.

Rinko, in turn, is able to offer solidarity. It isn’t that she’s stopped hearing or being bothered by ugly comments—in fact, the script showcases not just overtly hostile comments but more subtly painful moments, like Rinko’s beloved high school teacher praising her career with the comment, “I told you, once you’re older you stop caring about your appearance.” What she has been able to do is change her perspective subtly, from wishing her body could change to wishing the world would, and she found a partner who supports her (who is also a woman, in another moment of casual inclusiveness).

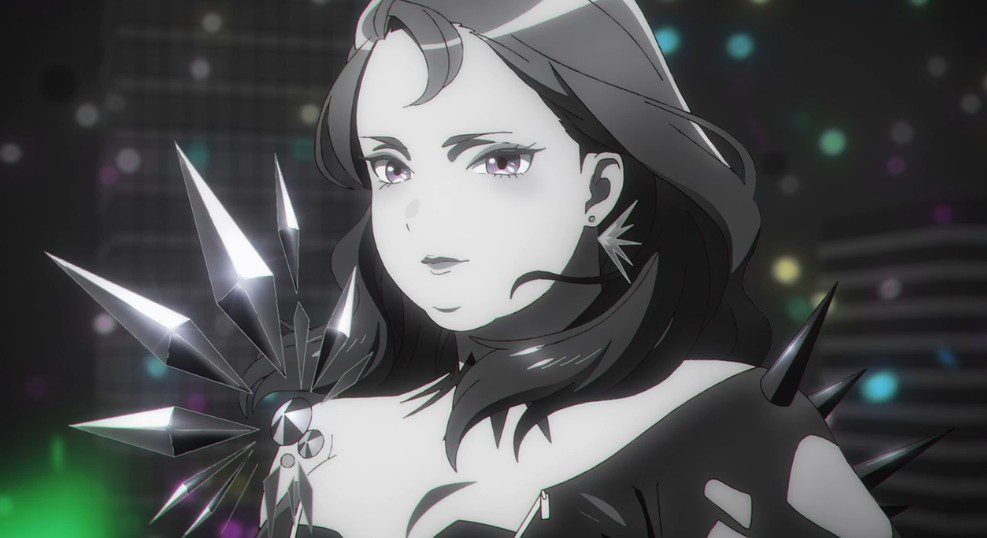

In revealing her lingering insecurities to Azu, Rinko tries to make her life feel like something the teenager can achieve someday herself. And being able to say that it’s hard, that the fourteen year old hasn’t failed for not already being an enlightened and unbothered fat icon, is what allows Azu to let down her walls ever-so-slightly. The “magic” she performs for Rinko is an ode to confidence, but the visuals emphasize the armor and sharp edges needed to keep walking toward that goal in an antifat society and world. The show’s musical numbers remain a strong point throughout, but few achieve the level of interwoven visual storytelling as this episode.

The musical number makes for a lovely bow on things: Rinko finds the courage to turn the job offer down, wanting to create a better future for the girls she met; and while Azu has to apologize to Rinko, the girls don’t force her to reveal the secret that’s troubling her. It’s a nice conclusion that keeps with Maebashi’s general ethos of storytelling. Each girl faces an issue that’s common for girls their age and their stories bring them to light and offer solidarity and commiseration. The show doesn’t offer any revolutionary upheavals of the status quo, but instead showcases small but actionable ways that girls the protagonists’ age could improve the world around them.

For most of the girls, this is contained to one or two episodes in the spotlight, with the sense that they’re continuing to make progress in the background afterward. But Azu’s struggles with her self-image are the show’s most consistent recurring subplot. When the girls’ shop is stolen by a rival apprentice, Azu despairs because it means she’ll be seen without her magical disguise. And while the other girls are quietly understanding, ditzy heroine Yuina offers one consistent response: that Azu should be allowed to look how she wants. That could potentially be a way for a writer to shrug off a subplot about weight loss and the social pressures that inform it, except for the fact that it’s Yuina who says it, making it much more meaningful.

Yuina is Maebashi’s secret weapon, a socially awkward but goodhearted girl in the mold of Sakura. She’s written to model inclusive behavior without being conscious of doing a Virtuous Thing. While she struggles with social cues, it comes naturally to her to treat others fairly and with kindness. She regularly praises Azu as being cute and fashionable, and that doesn’t change when she meets the “real” Azu. To Yuina, weight is a completely neutral fact about a person and what she’s dazzled by is Azu’s confidence and stylishness. What distresses Yuina, in turn, is the idea that Azu might be unhappy with how she presents herself. Her worldview is framed around choices a person makes to achieve their own style, and weight is no more notable than hair color. It’s also worth noting and praising that both Rinko and Azu are deliberately drawn to be cute in their own right, rather than “before” images waiting for some thin ideal. It’s a notable thing, given how common it is to see young artists struggling to depict fat bodies or being shamed for doing so.

It’s hard to overstate how moving this simple writing choice is. English-language writing spends a lot of time frothing over Japan as this utopia where there are barely any fat people. All one needs to do is simply look at how multiple outlets frame the Metabo Law, a 2008 ruling that measures employees’ waistlines and fines companies if those who exceed the standard do not lose the weight. No one should be shocked to learn that it’s untrue and that Japanese feminists are having conversations about fatphobia, whether we hear them or not. Eating disorders have been a growing issue in Japan for several decades, and one study found that one third as many adolescent boys showed signs of anorexia nervosa versus adolescent girls. In an era where fatness is still equated to being a personal failure, Maebashi has something empowering to say.

The final episode of Maebashi includes an extended dream sequence in which Yuina imagines the girls’ future as a squad of full-fledged witches. At first it seems that Azu has gotten her wish, walking the streets with the other girls in her thin form—but instead, the pattern has been reversed. Once they arrive back at the shop, Azu returns to her larger body; moreover, she eats with the other girls, something she continually rejects doing during the series (likely due to fear of being judged). While the other girls are surprised that she doesn’t stay thin all the time, given the option to do so, Azu responds that both versions of herself feel like the real her, and she hasn’t decided which she likes better. In effect, Azu has created a way to pass through the world without feeling constant pressure and degradation, while existing freely in a safe space with loved ones. It’s a fantasy that’s hard to deny to anyone whose body is stigmatized, and to write a girl who’s allowed to feel conflicted about still wanting to achieve social beauty standards, while giving her room to embrace herself as she is, feels very much like magic.

There’s been an encouraging uptick in titles over the past few years that include fat characters in an unremarked upon way–characters who not only exist beyond jokes about their weight or woes about dieting, but who are designed to look not just neutral but cute to the audience. It warms me to see the likes of Lilique, who’s loved by her friends and popular with boys, or the lovely love interests of SHWD and She Loves to Cook, She Loves to Eat. It’s heartening to see indie fashion brands embrace plus-size clothing options, and I encourage more people to read the beautiful Embrace Your Size. But I also have a special place in my heart for characters like Azu and Manly Appetites’ Otsu, who are prickly and sour and struggling with a society that hates them for existing…and who are told that they still deserve to be loved, just as they are.

Source link

cats] , , #Maebashi #Witches #sets #standard #tackling #fatphobia, #Maebashi #Witches #sets #standard #tackling #fatphobia, 1758951158, maebashi-witches-sets-a-new-standard-for-tackling-fatphobia