Spoilers for Revolutionary Girl Utena

Women are a pivotal element in my work. In my pictures they act as representatives of all genders….I process the human themes with a female cast.

Xenia Hausner, Austrian painter

Utena crossdresses to capture a boy’s [sense of adventure] while remaining a girl. To make a stand against the world.

A commodified form of femininity is sweeping pop culture online: from tradwife influencers getting millions on views on platforms like TikTok, to the chorus of No Doubt’s “Just a Girl” being used as a meme sound for young women to joke about how hopeless they are. Whether all of these posts are ironic or not, they reinforce a broader social trope about being “just” girls: pretty, pure-hearted, in need of rescue. Won’t somebody please care for girls who are just girls? Sentiments of this manner are not new, but they popped up in stronger frequency sometime during the pandemic and show no signs of stopping. Unthreatening femininity is en vogue, feminism old-fashioned and unnecessary. Images of womanhood beyond it are fringe and unattractive, if not outright non-existent.

It’s a deeply frustrating ecosystem to have to scroll through, particularly as a queer woman of color. It’s all the sweeter, then, to encounter modes of womanhood that are perpendicular to such notions. Sailor Moon S (1994-1995) and Revolutionary Girl Utena (1997) both feature butch characters very prominently: Tenoh Haruka, aka Sailor Uranus from the former, and Tenjou Utena, the titular protagonist of the latter. In adapting both these characters for TV, Ikuhara Kunihiko makes compelling arguments: that girlhood can look like many different things, that the girl who embraces masculinity finds herself with more freedom, and that it’s worth our while to deconstruct and question the archetypes and assumptions of girlhood that try to pin these characters down.

Depictions of butch, masculine, or more gender-non-conforming sapphic women are very rare in both Anglophone literature and animanga, though they make up a foundational part of shoujo. Haruka and Utena are icons of the 1990s, but they have been joined by very few others in the years that have passed since then. Works like the Boyish² Butch x Butch Yuri Anthology have worked to fill this gap, but less-feminine female characters rarely appear in modern mainstream anime, queer stories or otherwise, unless they are treated as unusual (as in the initial concept of Tomo-chan Is a Girl), villainous/tragic (see Attack on Titan’s Ymir), or end up embracing femininity as part of their character development. This makes Utena and Haruka, butch female characters who are treated positively and hold center stage in their narratives, noteworthy even after all this time. They’re a beacon if you’re looking for representation of this kind of girlhood, and the connections between them deserve special attention.

Tenou Haruka: The Perfect Boyfriend & Sailor Guardian

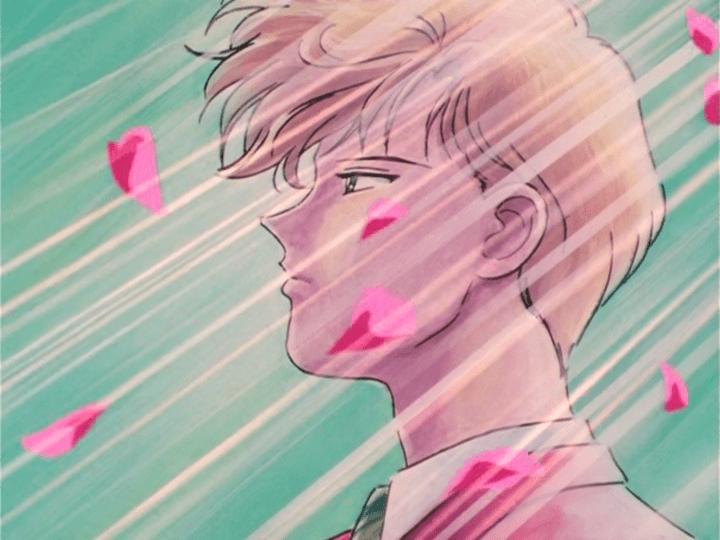

In Haruka’s debut episode, “A Handsome Boy!? Haruka Tenoh’s Secret”, Usagi and Minako encounter Haruka at the arcade that Usagi frequents. Usagi and Minako immediately assume she’s a man. It makes sense, in a way: Haruka is no different-looking than Motoki, the arcade clerk and another one of their crushes. The difference lies in how the show treats Haruka visually: Motoki does not get special shading and rose petals all over the screen just by appearing. Haruka receives these every single episode. Only when Haruka shows up the next day with her coat taken off, Usagi and Minako are shocked: that’s not the man of their dreams—Haruka is a girl!

The fact that Haruka is a girl does not even remotely dent her attractiveness to any of them. “She’s a girl, but…” is a common refrain. Makoto downplays her attraction to Haruka: she finds Haruka “cool” and that’s all there is to it. When Usagi relays news of Makoto going on a date with a girl to the other Guardians, Minako exclaims, in the Viz Media dub and its subtitles: “Did Makoto change her [sexual] orientation?” To which Usagi answers, “No, no, it’s just Haruka.” What to make of this statement? Haruka is not a girl, not yet a woman; for that matter, Haruka is neither man nor woman to the Guardians. She is unfamiliar and therefore exciting, which makes her safe to like.

One could argue this notion of Haruka “not being a girl,” and thus existing in a separate category, is somewhat of a copout (though surely not as big as the original American dub turning the two obvious lovers of Haruka and Michiru into cousins). But it feels consistent with how Haruka is seen in the show. Haruka defies categorization. As Sailor Uranus, she pursues her own mysterious goals, sometimes even opposite the other Guardians. As Haruka, she keeps her emotional distance to the others even as she keeps a charismatic facade. To save the world, she considers no sacrifice beneath her; it will hurt and it is cruel, but she considers it her life’s duty.

Unlike the other Sailor Guardians, she is not interested in men. She is more compelling and interesting for it, not less. That lack of a “prince” in her life makes her seem more mature; that she’s princely on her own gives her an air of independence. Her butchness registers within the show as capable of being both masculine and feminine at once. It’s this fact that drives much of Sailor Moon S.

Tenjou Utena: The Prince & Heroine

Stifled by a lack of creative freedom, S director Kunihiko Ikuhara left animation studio Toei in 1996. He assembled production studio Be-Papas with a number of previous collaborators and began conceiving a series about a “pretty girl with boy’s clothes” in the style of all-female theater group Takarazuka Revue. This was the first seed of Revolutionary Girl Utena, the anime of which entered production following its manga serialization.

As a young child, after having lost her parents, Utena is consoled by a prince and vows to become just like him. This she does: she refuses to wear the girls’ uniform, refers to herself in masculine pronouns, and plays with the boys. She may act like a boy, but don’t insult her: she’s not interested in being one. Her athletic and casually rebellious attitude makes her popular with the other girls, who love to fawn over her. But when she meets the mysterious Anthy Himemiya and challenges her abusive “owner” to a duel, Utena gets a chance to step into the “prince” role in a whole new way.

Utena is framed differently from Haruka as she is the protagonist, not a love interest or mysterious new character seen through the lens of familiar heroines. In the main series, she sports long, pink hair cut in a way that’s not at all masculine, and her athletic nature is highlighted more often than her butchness; Haruka, meanwhile, is the picture of machismo reminiscent of Mars’ male lead, Rei Kashino. But like with Haruka, POV shots of Utena abound that show her framed by roses and sparkles that signify her attractiveness to the girls watching. Throughout Utena the flowers play a prominent motif and typically symbolize romance. So when petals fly all across the screen while Utena plays basketball, it makes for a rosy view of her. She, at her best, is different from the others, queer in every sense of the word: a butch.

But while Haruka is secure and confident in her identity and hedges doubts when it comes to her mission, Utena is the opposite. Nothing could shake her from her quest to become a prince. Her identity, though, is not as rock solid as she makes it seem. Part of the reason why is their difference in age; Utena is in middle school, Haruka already in high school. Utena might be the character who nobly wants to save Anthy from Saionji’s abuse—even channeling the prince herself during crucial moments of the duel—but, as the introduction repeatedly suggests, there is a princess slumbering inside of her. By playing at princedom, Utena neglects another side of her personality.

In Utena’s worldview, her life is no more different than the other girls. After all, she too has a prince she yearns for. That she wants to become one is merely to fulfill his role in his absence. So when student council president Touga hints at being her prince, she falters. Despite her conviction to make Anthy (the objectified Rose Bride) “normal,” she loses. It reverts Utena to somebody meek and demure, one who wears the girls’ uniform and doesn’t speak up when she is harassed. But such a binary does not do her, or the world, any favors.

As Utena progresses, the prince role is revealed as nothing more than an impossible ideal, and this realization leads to despair, destruction, and misanthropy. Embodying the princess, too, leads to anguish. Anthy, originally a princess who “betrays” her prince by trying to save him rather than passively observing his suffering, must take on unbearable amounts of pain every waking hour as a focal point for the world’s misogyny. Utena violently rejects this idea. Freedom is attained when breaking free from the strict binary of masculine/feminine that such stringent roles are tied to. Being able to reject these notions and embrace an identity outside those parameters is what saves Utena, and Anthy with her. And the awareness of her difference, of the fact that nobility has nothing to do with gender per se, is what leads Utena to a truly heroic sacrifice in the final episodes.

World Shaking: The Absolute “Just A Girl” Apocalypse

I think of Utena looking forlorn when I think of the kind of sad, poor, victimized stereotype of being “just a girl” that so many of these social media posts espouse. It is not femininity itself that is the problem—both Sailor Moon S and Utena make this absolutely clear. After all, it is Usagi’s genre-defining magical girl selflessness that convinces Haruka of an alternate, death-free path to stop the Silence, and the more conventionally feminine Anthy and Wakaba bring Utena to the crucial path to self-acceptance. The problem is the enforcement of femininity and the restriction of girlhood into one neat, pink category. To expect every girl and woman to follow the same old template is unrealistic and leads to individual unhappiness, which translates to communal dissatisfaction. We can’t all be the same. There is room for every one of us to express ourselves freely, past the world of algorithms and trends.

Utena and Haruka’s non-conformities make all the difference—they show an alternate path on how to live as a girl in this world. Despite the large female cast, they are the only female characters in their respective series that can be called boyish. Other lesbian/bisexual female characters exist (Michiru in Sailor Moon; Anthy, Kozue, and Juri in Utena), but speak and appear very feminine. It is also noteworthy that the shows inspired by both Sailor Moon and Utena forego the butch character altogether. Princess Tutu (2002), an otherwise very charming show, posits that princesses can save princes, too; however, it eschews butch characters entirely for an extremely femme aesthetic. Puella Magi Madoka Magica (2011), on the other hand, uses the same color palette as Anthy and Utena (or Chibiusa and Hotaru), but Homura is just as feminine as Madoka is—a trait that’s stayed common with many modern pink/purple girl pairs.

The consistent theme in all these shows, that girls can (and do) save other girls, is a wonderful one. And it’s not to say the female characters in these series are all alike in personality or are all crammed into the same feminine mold. But by neglecting the butch character, girlhood becomes and remains a narrow corset. To their loss, they do not consider that gender and gender expression itself as a construct from which one can escape.

In 2000, Ikuhara was asked about the revolutionary aspect of Utena, to which he answered: “She revolutionizes herself as well as the world around her. From now on, she’s going to oppose and discover the world.” (emphasis mine) She cannot revolutionize herself and the world around her if she is not diametrically opposed to traditional femininity in the first place. She cannot rescue Anthy from it if she doesn’t see the corset and its pitfalls, its lack of logic. Why shouldn’t a girl get to do and be everything she wants to be? Why shouldn’t she get to be boyish if that’s what she wants? Why shouldn’t she be able to dream of it? By opposing the world, she is able to discover it, and to change it for the better.

Machismo, pride, sensitivity, self-servitude, bravery, compassion—all these things are within all of us, and embracing the “yang” to the much-yearned for “yin” leads us to fuller and stronger lives. The world is cruel enough; one need not make themselves even more open to its many ways of inflicting violence, least of all through stereotyping oneself. I’m not “just a girl”. I’m a woman. I’m human. Let me follow in the rose-petal footsteps of characters like Haruka and Utena, and let it be messy and complex and contradictory all at once.

Source link

cats] , , #Sailor #Moon #Revolutionary #Girl #Utena #butchness #vital #fluidity, #Sailor #Moon #Revolutionary #Girl #Utena #butchness #vital #fluidity, 1749745452, in-sailor-moon-s-and-revolutionary-girl-utena-butchness-is-vital-fluidity