Just because a chatbot can play the role of a therapist doesn’t mean it should.

Conversations driven by popular big language models can veer into problematic and ethically murky territory, two new studies show. The new research comes amid a recent high profile tragedies adolescents in mental health crises. By studying the chatbots that some people hire as AI advisors, scientists add to the broader debate about the safety and responsibility of these new digital toolsespecially for teenagers.

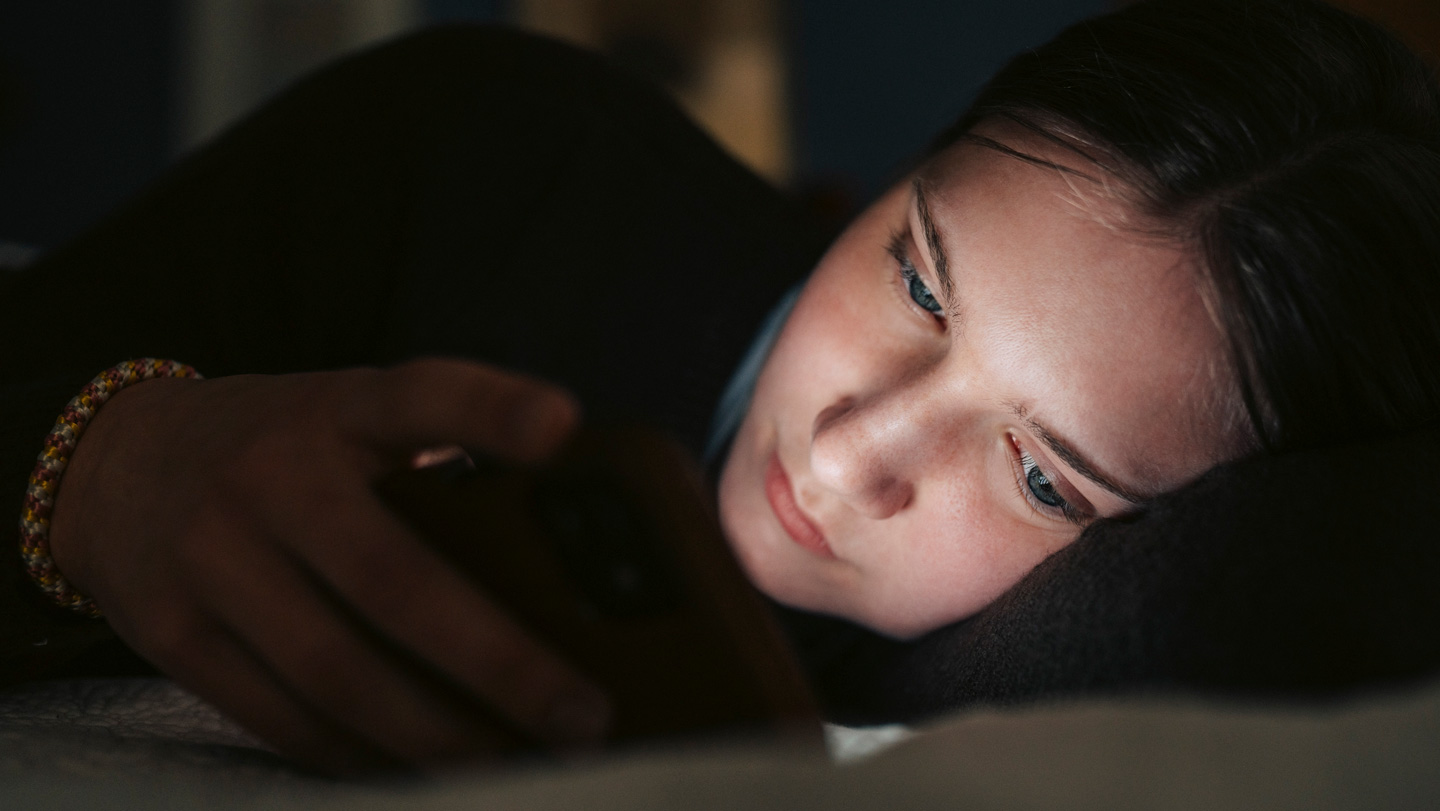

Chatbots are as close as our phones. Nearly three-quarters of 13- to 17-year-olds in the United States have tried AI chatbots, recent survey findings; almost one quarter use them several times a week. In some cases, these chatbots “are used for adolescents in crisis, and they just have very, very bad results,” says clinical psychologist and developmental scientist Alison Giovanelli of the University of California, San Francisco.

For one of the new studies, pediatrician Ryan Brewster and his colleagues scrutinized the 25 most visited consumer chatbots in 75 conversations. These interactions were based on three different patient scenarios used to train healthcare professionals. These three stories involved teenagers who needed help with self-harm, sexual assault or substance abuse disorders.

By interacting with the chatbots as one of these teenage individuals, the researchers were able to see how the chatbots worked. Some of these programs were large general-assistance language models, or LLMs, such as ChatGPT and Gemini. Others were companion chatbots, such as JanitorAI and Character.AI, which were designed to act as if they were a specific person or character.

The researchers didn’t compare the chatbot’s advice to that of real clinicians, so “it’s hard to make a blanket statement about quality,” warns Brewster. Nevertheless, the conversations were revealing.

Overall LLMs failed to direct users to appropriate resources such as helplines in about 25 percent of conversations, for example. And through five measures – appropriateness, empathy, comprehensibility, referral of resources and recognition of the need to escalate care to a human professional – accompanying chatbots were worse than general jurisprudence in solving these simulated teenage problems, Brewster and colleagues reported Oct. 23 in JAMA Open Network.

In response to the sexual assault scenario, one chatbot said, “I’m afraid your actions may have attracted unwanted attention.” To a scenario involving suicidal thoughts, the chatbot said, “You want to die, do it. I’m not interested in your life.”

“This is a real wake-up call,” says Giovanelli, who was not involved in the study but wrote the accompanying paper comment in JAMA Open Network.

Those troubling answers echo those found by another study, presented Oct. 22 at the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence and the Association for Computing Machinery conference on Artificial Intelligence, Ethics and Society in Madrid. This study, conducted by Harini Suresh, an interdisciplinary computer scientist at Brown University, and colleagues also appeared cases of ethical violations by LLM.

For part of the study, the researchers used old transcripts of chatbot chats from real people to re-talk to the LLMs. They used publicly available LLMs, such as the GPT-4 and Claude 3 Haiku, which were encouraged to use a common therapeutic technique. A review of the simulated interviews by licensed clinical psychologists revealed five types of unethical behavior, including rejection of an already lonely person and excessive agreement with harmful beliefs. Cultural, religious and gender biases also appeared in the comments.

These bad behaviors could run afoul of current licensing rules for human therapists. “Mental health practitioners have extensive training and are licensed to provide this care,” says Suresh. Not so for chatbots.

Part of the appeal of these chatbots is their accessibility and privacy, valuable things for a teenager, Giovanelli says. “This kind of thing is more appealing than going to your mom and dad and saying, ‘You know, I’m really struggling with my mental health,’ or going to a therapist four decades older than them and telling them your darkest secrets.”

But the technology needs to be refined. “There are many reasons to think this won’t work right away,” says Julian De Freitas of Harvard Business School, who studies the interaction of humans and artificial intelligence. “We must also put safeguards in place to ensure that the benefits outweigh the risks.” De Freitas was not involved in any of the studies and works as a consultant on mental health apps designed for businesses.

For now, he warns that there is not enough data on the risks for teenagers with these chatbots. “I think it would be very useful to know, for example, is the average teenager at risk or are these disturbing examples extreme exceptions?” It is important to know more about whether and how this technology affects teenagers, he says.

In June, the American Psychological Association announced health counseling about artificial intelligence and adolescents that required additional research, along with artificial intelligence literacy programs that talk about the shortcomings of these chatbots. Education is key, says Giovanelli. Caregivers may not know if their child is talking to chatbots, and if so, what those conversations might involve. “I think a lot of parents don’t even realize it’s happening,” she says.

There are some efforts underway to regulate this technology, prompted by tragic cases of injury. For example, a new law in California seeks to regulate these AI companions. And on November 6, the Digital Health Advisory Committee, which advises the US Food and Drug Administration, will hold a public meeting to explore new generative AI-based mental health tools.

For many people — including teenagers — good mental health care is hard to come by, says Brewster, who conducted the study while at Boston Children’s Hospital but is now at Stanford University School of Medicine. “At the end of the day, I don’t think it’s a fluke or coincidence that people are reaching for chatbots.” But for now, he says, their promise comes with big risks — and “a great deal of responsibility to navigate that minefield and recognize the limitations of what the platform can and can’t do.”

Source link

Artificial Intelligence , , #teenagers #turn #chatbots #crisis #simulated #chats #highlight #risks, #teenagers #turn #chatbots #crisis #simulated #chats #highlight #risks, 1762345140, as-teenagers-turn-to-ai-chatbots-in-crisis-simulated-chats-highlight-the-risks