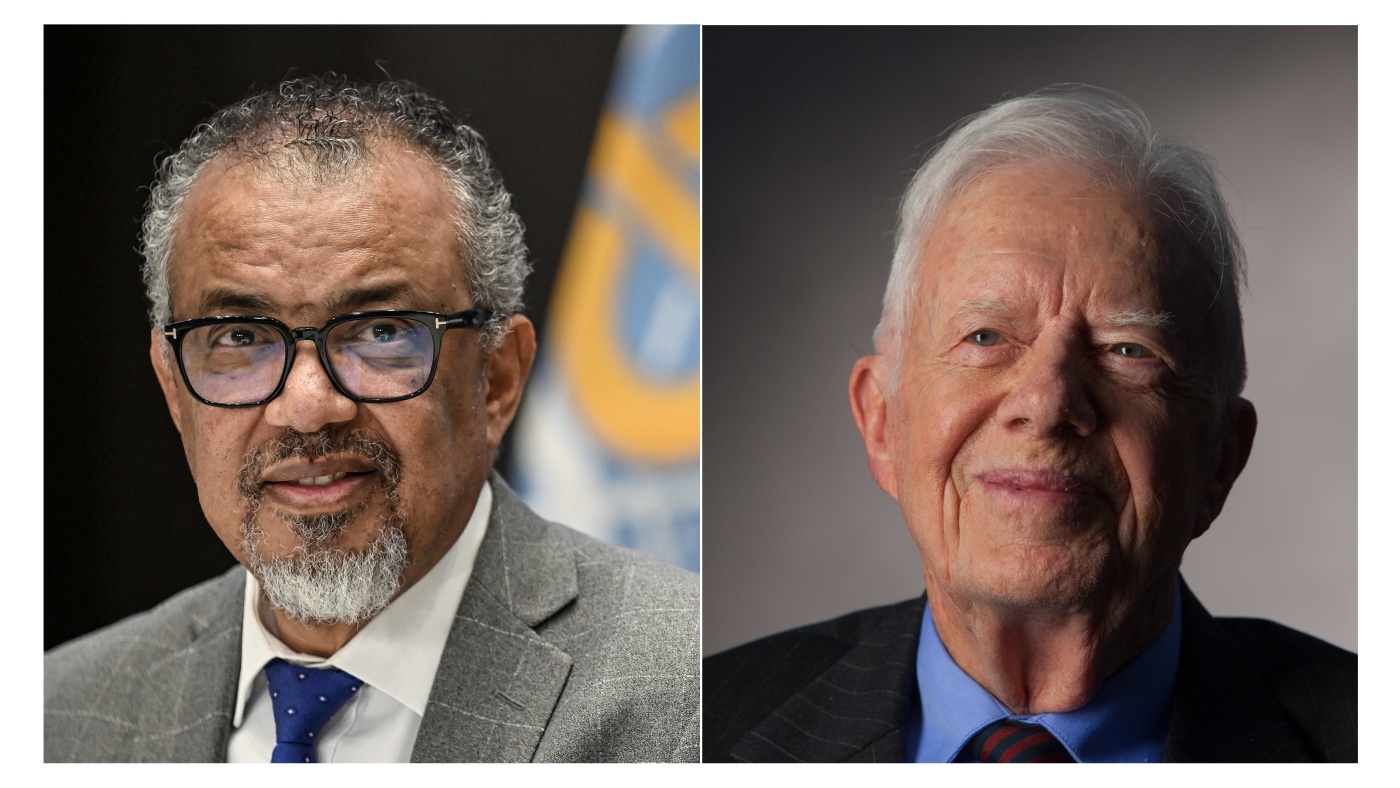

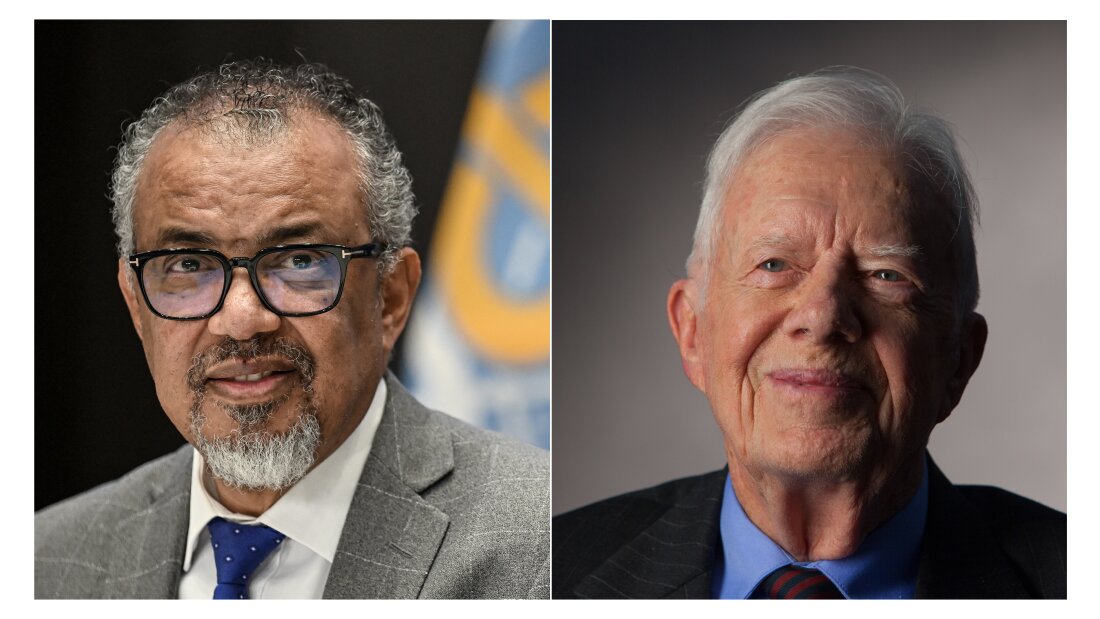

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and President Jimmy Carter met 20 years ago and developed a close relationship. Tedros says: “One thing that came to mind today at the funeral was President Carter’s humility. He was a humble leader and respected everyone, whether they were rich or poor or powerful or not. It didn’t matter to him.”

From left: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP; David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

Hide caption

Toggle label

From left: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP; David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images

The late President Jimmy Carter and Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus – the director general of the World Health Organization – knew each other for 20 years.

And they obviously had great respect for each other. In 2011, Tedros was the first non-American recipient of the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Humanitarian Award. In 2023, Rosalynn Carter received the WHO Global Health Prize for her work on mental health issues. The Carters supported Tedros’ bid to become the first African elected director-general of the WHO.

It’s not just that both men worked in global health and were active in the same circles. Behind the top-class awards is a close and long-standing friendship.

“I will cherish our relationship forever. I consider him my mentor – I learned a lot from him. His compassion is very, very contagious,” Tedros said Thursday after attending Carter’s funeral that morning. “I think the world has lost a very special person.”

As Tedros boarded the train to leave Washington, D.C., he shared his memories and thoughts about Carter with NPR. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

As you sat at the funeral today, did a memory of Carter come to mind?

One thing that came to mind at the funeral today was President Carter’s humility. He was a humble leader and respected everyone, rich or poor, powerful or not. It didn’t matter to him.

How did you meet Carter?

I’ve known him for more than two decades – to begin with [when I was] Minister of Health of Ethiopia and Second Director General of the World Health Organization.

One thing I remember – this was actually our first meeting in 2005 – we were expanding [Ethiopia’s] We launched a program to combat malaria and wanted to provide 10 million households with 20 million mosquito nets. And we secured 17 million mosquito nets while we were short of 3 million mosquito nets.

We discussed with [Carter] and his team about our work in the area of neglected tropical diseases. And I said, “Of course neglected tropical diseases are very important, but malaria is killing a lot of children as we speak.”

The answer [from Carter] was: “Okay! You’re down. You know the problem. You know the solution. That’s why we’re here to support you. “We don’t want to force anything or prescribe anything.”

It was just incredible. It shows how humble he was. It shows how truly respectful he was.

And of course came the 3 million mosquito nets – worth more than $15 million. And he came to Ethiopia in 2007 to distribute mosquito nets. That tells you a lot.

NPR reported on how Carter took on Guinea worm although there is neither a vaccine nor a cure for this painful parasitic infection. Its success is due to a fundamental public health approach – motivating behavior change and obtaining clean water. Billions are spent on medicines and treatments in global healthcare. What can we learn from the Guinea worm eradication strategy?

We see how important it is to strengthen the community. It starts with awareness – making sure communities understand the problem, the science, why it occurs, and what tools we have to stop it. And then find local solutions [like training community volunteers to identify the disease and care for the patients] and non-medical solutions [like simple mesh water filters].

When the eradication began three decades ago, the number of cases worldwide was more than 3.8 million. And now there are 13 or 14 cases – it’s almost over. When you strengthen communities and find local solutions, you can do a lot.

Carter is famous for his work on Guinea worms. Is there anything else that is close to his heart that sticks in your mind?

The other thing I think he would have focused on was capacity building. It is the Carter Center that helped us launch the Ethiopian Public Health Training Initiative. He strongly believed in community empowerment and training of national health professionals. So that would have been my priority, I think.

How did he cope with inevitable setbacks and frustrations?

He is very calm when a challenge comes. Because he is calm, he can see the solutions clearly. I saw that.

For example, there has been progress in the development of Guinea worm in many countries. And then there was news from some countries where elimination has already been declared: new cases were discovered. A lot of people were really unhappy, depressed and angry, frustrated. “Oh, why? Why is that? Why is that?’

He said, “No, no, calm down.” “Let’s see what happened, understand the root cause and then find a solution.”

[Guinea worm eradication] is running very well now. And I hope we get to the end – that will be his legacy.

Tell us something about Carter that the public doesn’t know?

Here is one thing I can share with you. He helped me become Director General of the World Health Organization. When I started the campaign – this was more than seven years ago – he said to me: “Tedros, I can support you.” Then I said: “That would be an honor.” Then he got very specific and said: “I can Write letters to heads of state and government who I know support you.” And then he did. He sent a personal letter, a private letter, to many heads of state and government. This is actually very, very important for me.

Source link

, , #mentor #Goats #Soda #NPR, #mentor #Goats #Soda #NPR, 1736472414, i-consider-him-my-mentor-goats-and-soda-npr